We’ve got a guest blogger for this month’s newsletter entry. Below is an article written for publication by Cary Academy’s Dean of Faculty Martina Greene. She was asked to contribute a chapter to the recent Future Forwards book from the American School of Bombay’s Research and Development Team. This piece will provide insight into the development of Cary Academy’s blended learning courses, and it is also serving as a template for future R&D projects at CA. This fall, our Director of Technology and Innovation Karen McKenzie has launched our own R&D team as part of the CA Strategic Plan.

Mike Ehrhardt,

Head of School

Blazing the Trail for Blended Learning:

The Cary Academy Blended Learning Development Team

by Martina Greene, CA Dean of Faculty

The blended learning model is rich with potential to transform teaching and learning, but how does a school prepare faculty to design and implement blended courses and assess the impact of these courses on students? At Cary Academy, we decided to take a collaborative approach to the process by creating and funding a Blended Learning Development Team. This chapter will describe how we engaged this faculty cohort in a year-long process of professional learning, course development and evaluation that resulted in the successful implementation of seven new blended learning courses in our Upper School.

From an individual to an organizational approach

Our first venture into blended learning came in 2011, when Cary Academy launched a summer grant program to support individual faculty members wanting to experiment with the blended format. While the grant program did result in the design and implementation of a couple of blended courses, it did not generate any broader interest in or momentum toward a larger scale implementation of the blended format at our school. In 2014, we decided to change tack, moving away from the isolated efforts brought forth by our individual grant program to a clearly-defined organizational effort rooted in the work of a collaborative group. The result was the launch of the Blended Learning Development Team.

Team objectives

The Blended Learning Development Team was established with three major objectives:

- To design and implement a slate of high quality blended courses rooted in research-based promising practices and reflecting the mission of the school.

- To identify core design principles for blended learning emerging from the implementation and evaluation of these courses.

- To contribute to the creation of an online training course to support future blended course development.

Importantly, we did not select a specific model of blended learning at the outset for all team members to adopt. We instead gave team members the flexibility to experiment with a variety of blended structures and strategies, as long as those experiments were consistent with the following four defining aims of blended learning[1]:

- A substantial proportion of the learning in the course (30-79%) takes place outside of the physical classroom in an online learning environment.

- The face-to-face and online components of the course are tightly connected in an online platform to provide an integrated learning experience.

- Learners experience increased control over the time, place, path and/or pace of their learning.

- Learners experience enhanced opportunities for engagement with teacher, with peers, with content and with outside resources.

Choosing the courses to be developed

Teachers interested in becoming a part of the Blended Learning Development Team were invited to submit proposals describing how they hoped to use blended structures and strategies to better meet the needs of students in a given course. Seven proposals from a variety of content areas were ultimately accepted, each with a specific area of focus for leveraging the blended format:

|

Course

|

Focus

|

| Calculus I and II (Advanced) |

Using the blended format to support accelerated learning for talented and highly-motivated students. |

| Creative Writing |

Using the blended format to enhance coaching and peer feedback in support of individual projects. |

| Environmental Science (Advanced) |

Using the blended format to support student-directed project-based learning. |

| Great Books (Advanced) |

Using the blended format to expand participation in discussions and to improve the quality of contributions to discussions. |

| Global Leadership |

Using the blended format to facilitate team teaching and student collaboration involving multiple schools. |

| Music Theory (Advanced) |

Using the blended format to give students choice in pathway and to support the creative use of music-specific technology tools. |

| Physics |

Using the blended format to enable students to work at their own pace toward mastery of key concepts. |

By creating a vehicle for pursuing these seven individual experiments within a team setting, we were able to generate an ongoing flow of ideas from which all members of the team could draw. In so doing, we were able to bring much-needed synergy to our school’s blended learning initiative.

Building the team

The Blended Learning Development Team began its work in June 2014 with a two-week program of collaborative course development centered on the creation and critique of a prototype module for each course. Cary Academy partnered with the Virtual High School Collaborative to create a set of training materials to support team members in the development of the online infrastructure for their courses. These materials addressed a variety of topics, including organization and learner support features, facilitation of online discussions, strategies for promoting online collaboration, and use of the virtual space for formative evaluation and feedback. We also arranged for faculty from North Carolina State University College of Education, the Friday Institute for Educational Innovation, the Virtual High School Collaborative, and the North Carolina Virtual Public High School to help review the course modules created. Team members then spent the remainder of the summer using their vetted prototype units as models for building out the rest of their courses. The team’s work continued during the academic year with biweekly meetings focused on idea sharing and problem solving, review of student feedback, group tuning of course modules, and identification of emerging design principles and best practices.

Course evaluation model

Course evaluation was from the beginning a key component of the vision for the Blended Learning Development Team. To that end, Cary Academy partnered with two research scholars from the Friday Institute for Educational Innovation to help us assess the impact of our blended courses upon student learning through development and implementation of a formal course review protocol. The researchers began by working with the team to develop a set of indicators for effective blended learning informed by a review of relevant literature, existing standards for blended and online learning, and the specific goals of team members. From there, the researchers helped the team create two student surveys, one given at the beginning of the year to capture student perceptions of blended learning entering into the courses, and one more in-depth survey toward the end of the year to capture student perceptions of their experiences in the blended courses. Our research partners also conducted a mid-year student focus group with a mix of students from all seven courses to collect feedback and recommendations for improving various elements of the courses. To round out the process, the researchers conducted two teacher interviews, one at the beginning of the year to register the teacher’s initial approach to course development, and a second interview at mid-year to document changes the teacher made to the course and to capture emerging best practices from the teacher’s perspective.

General outcomes

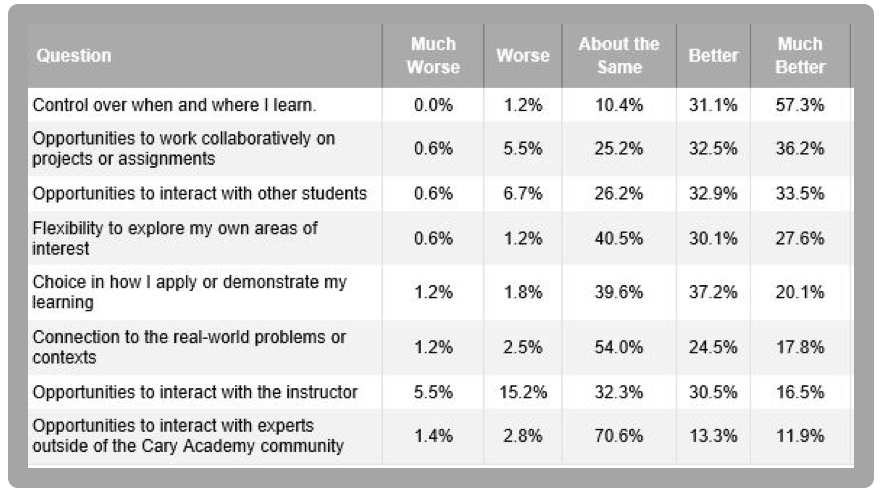

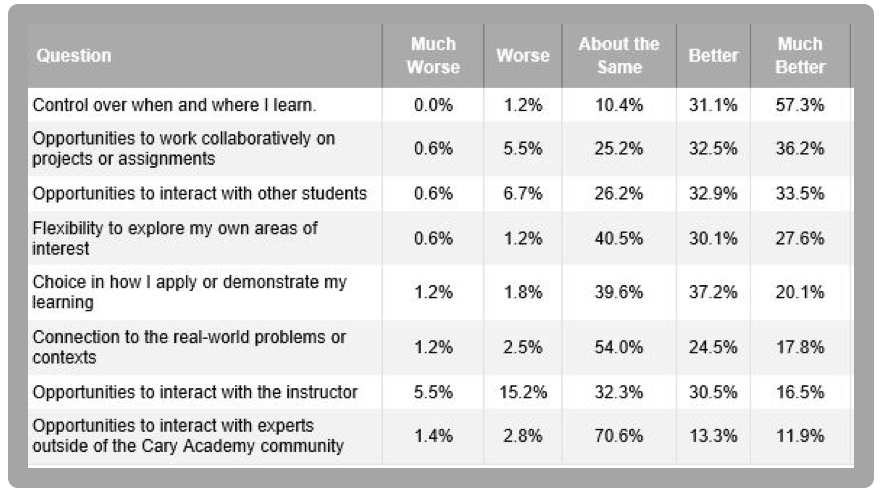

The table below shows some of the general outcomes of our blended learning initiative captured in survey data collected from the 139 students enrolled in blended courses in 2014-15:

Students clearly felt that the blended format gave them greater control over the time and place of their learning, with 88% of students reporting that their blended course was either better or much better in that regard. Students also felt that they had greater opportunities to interact and collaborate with peers in the blended format, with two-thirds of students reporting improvement over a traditional course. In addition, the majority of students indicated that they experienced greater flexibility to explore their own areas of interest and greater choice in how they demonstrated their learning. Nearly half the students saw improvement in opportunities to interact with the teacher as well, but it should be noted that this perception varied significantly from course to course and even within some of the courses. When it came to opportunities to interact with experts outside of the Cary Academy community, however, 70% of students found no improvement with the blended format. Those students who did report improvement in that area were mostly in the Global Leadership and Advanced Environmental Science courses.

The power of the digital platform

The qualitative data we collected from teachers and students also provided a number of interesting insights into the effectiveness of our blended learning initiative, starting with the power of the electronic infrastructure that team members worked so hard to design for their courses during the summer institute. As expected, in the absence of daily face-to-face contact with the teacher or with fellow students, the digital platform became the nexus for information-sharing and management of the learning process. Students reported much greater use of communication features like announcements, private messages, chat and discussion boards in their blended courses than in traditional courses operating with the same learning management system. Perhaps even more significantly, the digital platform also served to demystify the blended format for our community by capturing the learning that took place in our blended courses in highly visible ways. In each of our blended courses, one can easily see the engagement of the students with the subject matter, the individual and collaborative work produced by students in the effort to attain mastery, and the feedback sought and given—all preserved within the digital learning space. We hope that the success of our Blended Learning Development Team in leveraging the tools within our learning management system to facilitate meaningful communication and collaboration and to document student learning will inspire fuller utilization of the system’s features in our traditional courses, as well.

A positive shift in student culture

Conversations with teachers and students also revealed an important shift in student culture arising from our blended learning courses. The teacher group in particular reported that students no longer seemed to view face-to-face class periods in the physical classroom as teacher-controlled time and space. As the students became accustomed to taking more responsibility for their own learning outside of the physical classroom environment, they started assuming more responsibility for the learning within the physical classroom, too. For example, rather than arriving in class and waiting for the teacher to introduce the lesson plan for the day, the students began coming to class and talking to the teacher about what they thought would be the best way to utilize the class meeting time. We are eager to see whether this increased sense of ownership among students of their learning time will carry over to other classes, even those that are not blended.

Fostering more thoughtful discussion

Blended course teachers noticed a similar trend toward greater student responsibility in class discussions. The blended format necessarily shifts a substantial amount of discussion from the face-to-face classroom environment to the virtual environment. One of the major benefits of an online discussion forum is that it captures a written record of a discussion, thus providing teachers with a means to engage students in some meta-analysis of what makes a good discussion and how they can contribute effectively to discussions. Several of our blended learning teachers worked with students to create detailed rubrics to guide student contributions to online discussions and help students evaluate their contributions. As students internalized the techniques of effective discussion in the online forum, teachers noted improvement in the quality of participation in face-to-face discussions as well. We believe that this is another success stemming from our blended learning initiative that will positively impact student performance in all class settings.

Students as co-creators of course content

The value of online discussion forums within the blended model was by no means limited to helping students improve their contributions to class conversations. Teachers also reported using discussion boards in combination with other social media tools to engage students in defining the direction of the course. Our environmental science teacher, for example, created a system for “crowdsourcing” course content by soliciting ideas from students through news discussion threads, green tweets, and student-generated mini-lessons posted to a blog. Each student in the course contributed to a weekly online discussion group by starting a discussion thread for an environmental news story that piqued his or her interest and by responding to at least one other thread started by someone else in the group. Students were also asked to scour Twitter for what they considered to be the most intriguing tweets on the environment and to retweet at least one of those tweets each week to the class. Last but not least, students were expected to work in groups to develop short lessons on environmental topics of interest, which were posted to a blog with opportunities for peers to comment. The discussion threads, tweets, and mini-lessons that resonated most with members of the class then became the topics for more in-depth exploration by the entire class through labs and project work. Evidence of the success of this effort to give students greater voice in the direction of their learning can be seen in the student survey data for this specific course. 73% of students in environmental science reported better or much better flexibility to explore their own areas of interest, 86% of students reported better or much better choice in how they applied their learning, and 93% of students reported better or much better connection to real world problems or contexts. These results were well above the already noteworthy outcomes in these areas for our blended courses across the board.

The value of self-paced learning

While all of our blended courses aimed to give students greater control over the time, place, path and pace of their learning, one course in particular stood out in providing students with a self-paced, mastery-based learning experience. The physics teacher used the Meteor platform to build a custom application called OpenLab to support student-driven learning rooted in a modeling approach. The OpenLab application enabled students to schedule and track themselves at their own pace through the collaborative and cyclical process of developing and deploying their models, while at the same time freeing the teacher to work with individuals or small groups to address specific learning needs as they arose. The course teacher reported that students in the blended physics course with OpenLab showed significant improvement in the Test of Understanding Graphs in Kinematics (TUG-K), moving from 28% to 75% when most high school students average only 40% upon completing an introductory physics course. This also marked the first time at Cary Academy that every student in the general physics course showed improvement. Although there is still much to be done to streamline and improve the OpenLab application, the initial results on an objective and standard assessment suggest that the increased student control over the pace of learning made possible by the blended format with OpenLab led to better mastery of core physics concepts. These results persuaded at least two other members of the Blended Learning Development Team to consider integrating the OpenLab application into their own blended courses as part of their own standards-based approach to teaching.

Next steps

Given the success of the Blended Learning Development Team in its first year, we decided to keep the team in place for a second year, with a focus on fine-tuning the courses created in year one based upon the results of the course evaluation data. We also invited faculty to submit additional proposals for blended courses to bring the total number of blended offerings to ten. Significantly, each of the new courses will include a focus on creating opportunities for students to interact with experts outside the Cary Academy community, an aspect of blended learning that we felt was not fully explored in our first year:

|

Course

|

Focus

|

| Architecture |

Using the blended format to create opportunities for students to apply their learning to real-world projects. |

| Calculus III (Advanced) |

Using the blended format to supplement a university-based course. |

| Human Anatomy and Physiology |

Using the blended format to facilitate the integration of outside experts and resources. |

Conclusion

The courses created and implemented by members of the Blended Learning Development Team have proven to be vivid examples of the potential of the blended model to transform teaching and learning. The success and popularity of these classes has also generated the momentum we were seeking toward a larger scale implementation of the blended format. We expect blended learning to evolve from its current status as an experimental course structure to eventually become the norm for the creative and effective use of technology to enhance teaching and learning at our school. The Blended Learning Development Team has certainly helped us to blaze the trail in that direction.

[1] See Heather Staker and Michael B. Horn, Classifying K-12 Blended Learning (Innosight Institute, 2012).